Blog

An unmanaged retreat in Java

Posted 19th September 2020

Introduction

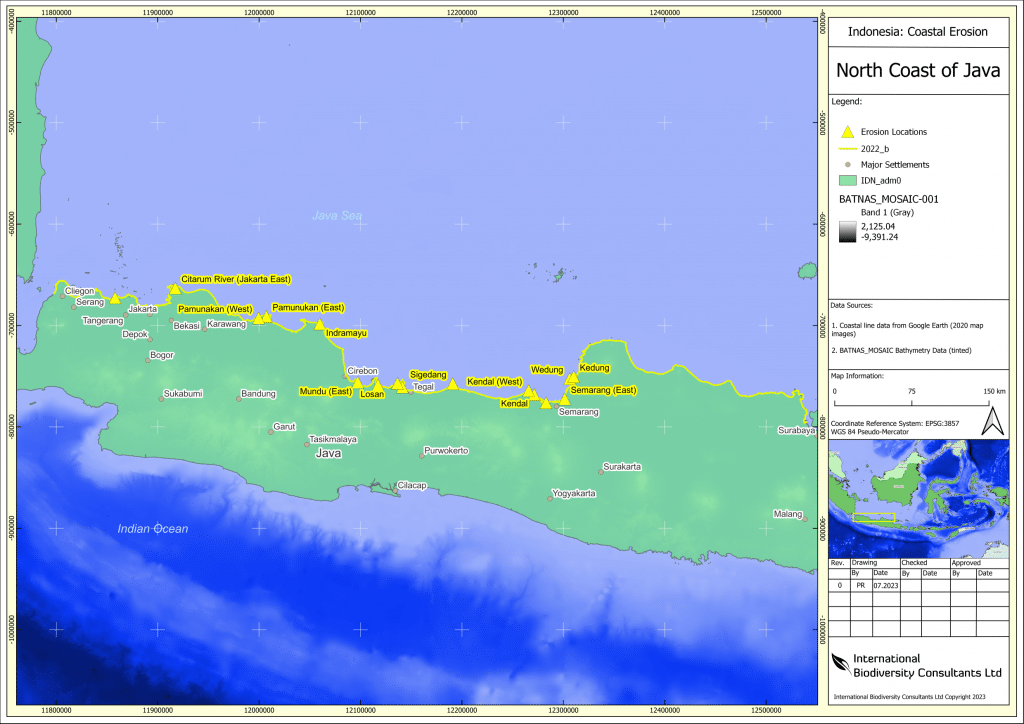

The coastline of Java in Indonesia, like many other coastal areas around the world, is vulnerable to the impacts of sea level rise due to a combination of natural and human factors. One of the primary reasons for Java’s vulnerability is its low-lying topography. The island has a long and heavily populated coastline that is mostly flat, with many areas located only a few meters above sea level. This makes these areas highly susceptible to flooding and inundation during high tides, storm surges, and other extreme weather events. Over the past decade, the north coast of Java has experienced an average sea level rise of 8 millimeters per year, which is one of the highest rates in the world. This sea level rise has already had significant impacts on the region, including coastal erosion, saltwater intrusion, and flooding of low-lying areas.

Figure 1. The North coast of Java indicating the number of locations impacted by coastal erosion. Click on image to enlarge.

In addition to its physical characteristics, Java’s vulnerability is exacerbated by human activities. The island’s coastal areas are heavily developed, with large population centers and critical infrastructure located close to the coast. This puts these areas at increased risk of damage from sea level rise, as well as from other climate-related hazards. Furthermore, the island’s population growth and rapid urbanization have led to the conversion of large areas of mangroves and other natural coastal habitats into urban areas, agriculture, and aquaculture. This has reduced the ability of the natural coastal ecosystems to provide protective services, such as erosion control and wave attenuation, which could have helped to mitigate the impacts of sea level rise.

Rise and sinking of a mega-city

The north coast of Java is home to some of the most densely populated areas in Indonesia, including the capital city of Jakarta. Jakarta is a massive city by global standards, both in terms of population and land area. According to Martinez and Masron (2020), Jakarta is currently the world’s second-largest urban area, with a population of over 30 million people living in its metropolitan region. The city covers an area of approximately 661 square kilometers (255 square miles), making it one of the largest cities in Southeast Asia. The north of the city area is also highly vulnerable to the impacts of sea level rise due to its low-lying coastal areas and rapidly expanding urban centers. As the city is built on a river delta, it is only a few meters above sea level and therefore has already experienced severe flooding in recent years due to a combination of heavy rainfall and high tides. Sea level rise is expected to exacerbate this problem in the future. In fact, a study by the World Bank (2021) has predicted that by 2050, up to 95% of Jakarta could be submerged by sea level rise and flooding (BBC, 2018).

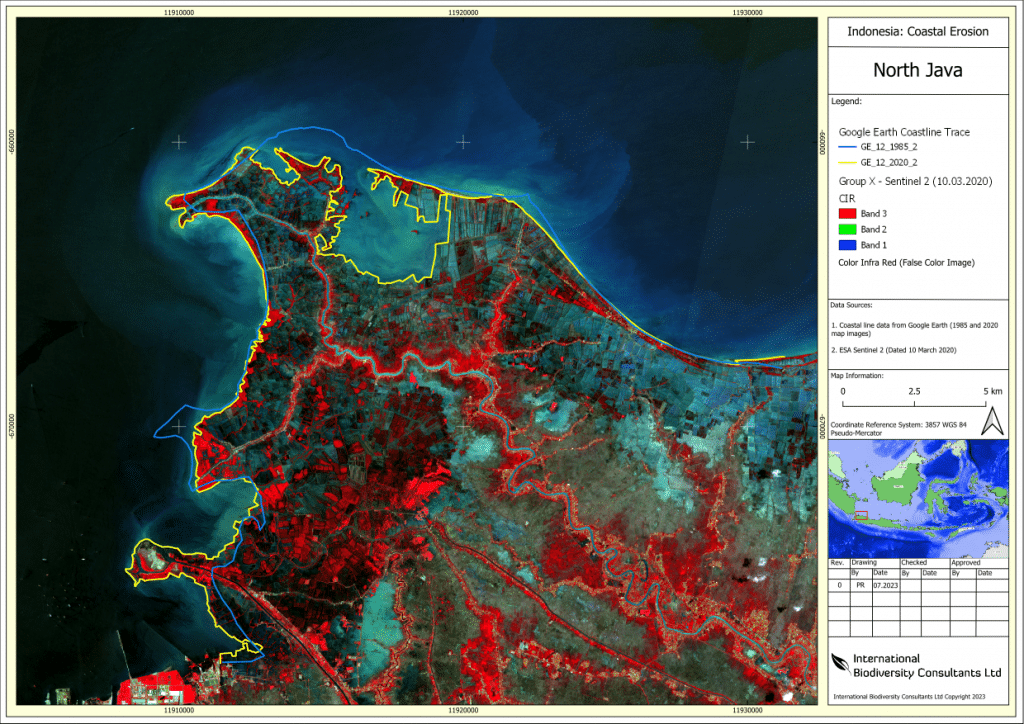

North-east of North Jakarta, there is a peninsular sheltering Jakarta Bay to the east (Figure 1 below), here the Citarum River meets the sea. It was also here that analysis of European Space Agency (ESA) Sentinel 2 satellite imagery appeared to show an extensive area reclaimed by the sea. Through analysis of the satellite images, we were also able to detect inland water levels, and identifying which areas are vulnerable. The peninsular is extensively used for aquaculture and fish farming with many square and oblong plots evident. A dyke system links up with the plots and possibly provides seawater on each tidal cycle. It was also clear that the seaward coastline had been breached in a couple of places and land had been reclaimed by the sea.

Figure 2. A Sentinel 2 False Color Image (FCI) satellite picture highlighting vegetation in red. The area is North East of Jakarta (North Java) showing in the center of the map a strip of coastline which has been breached by the sea and has flooded an inland area. Click on image to enlarge.

As global warming increases temperatures, sea level rise is impacting more around the globe, but especially to countries on the equator. This is well known and so we didn’t do much more with the maps, thinking that flooding in Jakarta city was where the focus laid. That is until Nivell Rayda (1), a journalist with the Channel News Asia covered a story on the peninsular and the people who struggle to live and work there (2). Nivell’s article does indeed reveal that the area of West Java was an epicenter for aquaculture supplying fish and shrimp products to Jakarta and its close proximity meant the area thrived. So successful was this trade that some farmers were earning up to US$10,000 every few months giving it the nickname ‘Dollar kampung’. People were attracted to the area and as a result, new farms and more farms were established. Today, this stretch of coastline is dominated by aquaculture. Talking with locals at Beting Village, Nivell found out that changes started to happen from 2008. Once breached, the sea quickly reclaimed the land as erosion processes destabilized the former coastline letting more seawater in.

Nivell states up to 6,000 ha have now been reclaimed by the sea. Villagers are fighting back by replanting mangrove trees in the hope that this may slow, stabilize or stop the erosion. However, aquaculture ponds by their nature require excavation of the ground to establish the boundary of the plot. Tidal forces are no match for loosened ground made of soft sediments.

Beyond Jakarta

Other areas on the north coast of Java that are vulnerable to sea level rise impacts (see Figure 1. above) include the towns of Cirebon and Brebes, which are home to large populations and critical infrastructure such as seaports and power plants. These areas are also at risk of saltwater intrusion, which can contaminate freshwater sources and make them unusable for agriculture and drinking water.

Java and Indonesia are crowded places, land is productive and heavily utilized for food production. People from coastal communities impacted by sea level rise are not only loosing homes and livelihoods, they are also having to relocate and enter a crowded market elsewhere. While flood defenses are a critical focus for Central Government, efforts are mainly focused on North Jakarta as a center for commerce, industry and residences (4) and a city with its own sinking problems too.

Moving forwards with solutions

Despite these challenges, there are some measures being taken to address the impacts of sea level rise on the north coast of Java. The Indonesian government has developed a National Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation that includes measures to protect vulnerable coastal areas, such as building seawalls and planting mangroves. In addition, communities are being encouraged to adopt sustainable land use practices and reduce their carbon emissions to mitigate the causes of climate change. Indonesia also possibly needs to ramp up the scale of Nature-based Solutions (defined by IUCN as “actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural or modified ecosystems…”) and large-scale planting of mangroves could be one solution to utilize which would also benefit marine ecosystems and biodiversity. However, more needs to be done to address the urgent threat of sea level rise on the north coast of Java. The region’s rapidly expanding population and urbanization make it even more important to take action now to protect vulnerable communities and ecosystems. By working together, the government, communities, and businesses can develop sustainable solutions that will help to safeguard the north coast of Java for generations to come.

About the Author: Dr. Phil Rogers is an international environmental and biodiversity specialist and is Director and Lead Ecologist for International Biodiversity Consultants Ltd. He is currently working in South East Asia and is based in Jakarta, Indonesia.

About International Biodiversity Consultants Ltd: International Biodiversity Consultants Ltd was formed in 2019 and is focused on global solutions for nature. Find out more here or link up with our social media: linktr.ee/ibioconsultants

This article was updated on July 2023.

References

- IUCN Global Standard for Nature-based Solutions, full definition of NbS, Accessed at: https://www.iucn.org/theme/ecosystem-management/our-work/iucn-global-standard-nature-based-solutions (29 August 2020)

- Liliansa, Dita (2023) Sea level rise may threaten Indonesia’s status as an archipelagic country, PHYS.ORG, 19 January 2023. Accessed at: https://phys.org/news/2023-01-sea-threaten-indonesia-status-archipelagic.html (15 April 2023).

- Martinez, Rafael and Masron, Irna Nurlina (2020) City Profile: Jakarta, a city of cities. Cities (Volume 106), November 2020, 102868. Accessed at:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102868 (15 April 2023) - Mayuri Mei Lin and Rafki Hidayat (2018) Jakarta, the fastest sinking city in the world, BBC News, London. 13 August 2018. Accessed at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-44636934 (15 April 2023)

- Nivell Rayda (2020) Time is running out for Indonesian fishing village as it battles coastal erosion. Accessed at: https://borneobulletin.com.bn/time-is-running-out-for-indonesian-fishing-village-as-it-battles-coastal-erosion/ (25 April 2023).

- Simanjuntak, I., Frantzeskaki, N., Enserink, B., and Ravesteijn, W. (2012) Evaluating Jakarta’s flood defence governance: the impact of political and institutional reforms, Water Policy 14 (2012) pp 561-580. Accessed at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/… (20 September 2020)

- World Bank Group and Asian Development Bank (2021) Climate Risk Country Profile – Indonesia. WBG, Washington and ADB, Manilla. Accessed at: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2021-05/15504-Indonesia%20Country%20Profile-WEB_0.pdf (15 April 2023)